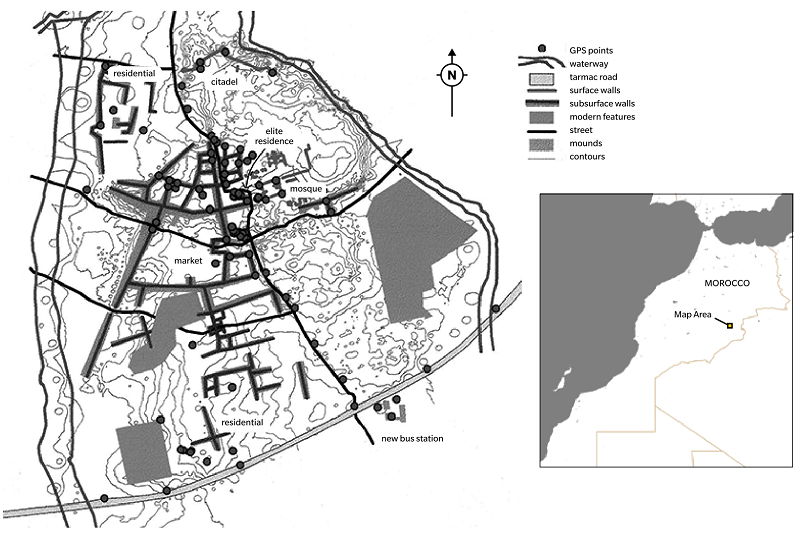

![Map of central Sijilmasa]() Plan of central Sijilmasa, located within the Tafilalt Oasis, produced by the Moroccan-American Project at Sijilmasa

Plan of central Sijilmasa, located within the Tafilalt Oasis, produced by the Moroccan-American Project at Sijilmasa

![The Bab al-Rih (Gate of the Wind) or Bab Fez (Gate to Fez)]() The Bab al-Rih (Gate of the Wind) or Bab Fez (Gate to Fez) stands at the northern limit of Sijilmasa. Ancient arcades over a portal were restored in a more recent era. Photograph by Kathleen Bickford Berzock, 2017

The Bab al-Rih (Gate of the Wind) or Bab Fez (Gate to Fez) stands at the northern limit of Sijilmasa. Ancient arcades over a portal were restored in a more recent era. Photograph by Kathleen Bickford Berzock, 2017

![Oil lamp excavated at Sijilmasa]() Oil lamp excavated at Sijilmasa (13 x 8.5 x 5 cm). Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

Oil lamp excavated at Sijilmasa (13 x 8.5 x 5 cm). Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

![Fragment of a water filter]() Fragment of a water filter excavated at Sijilmasa (9 x 6 x 3 cm). Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

Fragment of a water filter excavated at Sijilmasa (9 x 6 x 3 cm). Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

![ceramic fragments]() Cuerda seca ceramic fragments excavated at Sijilmasa (various dimensions). Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

Cuerda seca ceramic fragments excavated at Sijilmasa (various dimensions). Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

![Glazed ceramic fragments]() Glazed ceramic fragments excavated at Sijilmasa (various dimensions). Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

Glazed ceramic fragments excavated at Sijilmasa (various dimensions). Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

![Carved stucco fragment]() Carved stucco fragment excavated at Sijilmasa (47.5 x 28.5 cm). Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

Carved stucco fragment excavated at Sijilmasa (47.5 x 28.5 cm). Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

![Fragment of painted wall decoration]() Fragment of painted wall decoration, Sijilmasa, Morocco, 9th/10th century. Plaster, 21 x 19 cm. Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

Fragment of painted wall decoration, Sijilmasa, Morocco, 9th/10th century. Plaster, 21 x 19 cm. Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

![Ring]() Ring, excavated at Sijilmasa, Morocco, 9th/10th century. Gold, diameter 1.9 cm. Fondation nationale des musées du Royaume du Maroc, Rabat, 2006-1. Photograph by Abdallah Fili and Hafsa El Hassani

Ring, excavated at Sijilmasa, Morocco, 9th/10th century. Gold, diameter 1.9 cm. Fondation nationale des musées du Royaume du Maroc, Rabat, 2006-1. Photograph by Abdallah Fili and Hafsa El Hassani

![Vase inscribed with “al-Baraka,”]() Vase inscribed with “al-Baraka,” Sijilmasa, Morocco, 11th century. Glazed ceramic, 25.4 x 17.8 x 14 cm. Musée archéologique de Rabat, Morocco. Photograph by the Moroccan-American Project at Sijilmasa, 1988

Vase inscribed with “al-Baraka,” Sijilmasa, Morocco, 11th century. Glazed ceramic, 25.4 x 17.8 x 14 cm. Musée archéologique de Rabat, Morocco. Photograph by the Moroccan-American Project at Sijilmasa, 1988

Plan of central Sijilmasa, located within the Tafilalt Oasis, produced by the Moroccan-American Project at Sijilmasa

Plan of central Sijilmasa, located within the Tafilalt Oasis, produced by the Moroccan-American Project at Sijilmasa

The Bab al-Rih (Gate of the Wind) or Bab Fez (Gate to Fez) stands at the northern limit of Sijilmasa. Ancient arcades over a portal were restored in a more recent era. Photograph by Kathleen Bickford Berzock, 2017

The Bab al-Rih (Gate of the Wind) or Bab Fez (Gate to Fez) stands at the northern limit of Sijilmasa. Ancient arcades over a portal were restored in a more recent era. Photograph by Kathleen Bickford Berzock, 2017

Oil lamp excavated at Sijilmasa (13 x 8.5 x 5 cm). Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

Oil lamp excavated at Sijilmasa (13 x 8.5 x 5 cm). Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

Fragment of a water filter excavated at Sijilmasa (9 x 6 x 3 cm). Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

Fragment of a water filter excavated at Sijilmasa (9 x 6 x 3 cm). Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

Cuerda seca ceramic fragments excavated at Sijilmasa (various dimensions). Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

Cuerda seca ceramic fragments excavated at Sijilmasa (various dimensions). Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

Glazed ceramic fragments excavated at Sijilmasa (various dimensions). Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

Glazed ceramic fragments excavated at Sijilmasa (various dimensions). Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

Carved stucco fragment excavated at Sijilmasa (47.5 x 28.5 cm). Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

Carved stucco fragment excavated at Sijilmasa (47.5 x 28.5 cm). Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

Fragment of painted wall decoration, Sijilmasa, Morocco, 9th/10th century. Plaster, 21 x 19 cm. Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

Fragment of painted wall decoration, Sijilmasa, Morocco, 9th/10th century. Plaster, 21 x 19 cm. Ministère de la culture et de la communication du Royaume du Maroc. Photograph by Fouad Mahdaoui

Ring, excavated at Sijilmasa, Morocco, 9th/10th century. Gold, diameter 1.9 cm. Fondation nationale des musées du Royaume du Maroc, Rabat, 2006-1. Photograph by Abdallah Fili and Hafsa El Hassani

Ring, excavated at Sijilmasa, Morocco, 9th/10th century. Gold, diameter 1.9 cm. Fondation nationale des musées du Royaume du Maroc, Rabat, 2006-1. Photograph by Abdallah Fili and Hafsa El Hassani

Vase inscribed with “al-Baraka,” Sijilmasa, Morocco, 11th century. Glazed ceramic, 25.4 x 17.8 x 14 cm. Musée archéologique de Rabat, Morocco. Photograph by the Moroccan-American Project at Sijilmasa, 1988

Vase inscribed with “al-Baraka,” Sijilmasa, Morocco, 11th century. Glazed ceramic, 25.4 x 17.8 x 14 cm. Musée archéologique de Rabat, Morocco. Photograph by the Moroccan-American Project at Sijilmasa, 1988