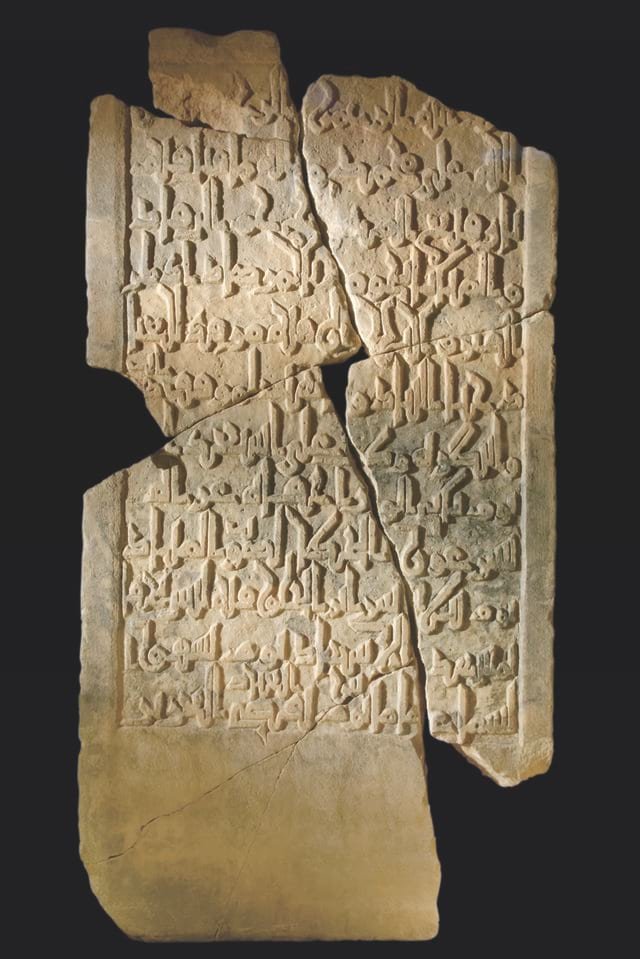

![Monument from Sane necropolis. Marble, 87 x 45 cm.]() Monument from Sane necropolis, Gao, Mali, 12th century. Marble, 87 x 45 cm. Musée national du Mali, Bamako, R88-19-279. © Marie-Lan Nguyen/Wikimedia Commons. Shared under CC-BY 4.0 license

Monument from Sane necropolis, Gao, Mali, 12th century. Marble, 87 x 45 cm. Musée national du Mali, Bamako, R88-19-279. © Marie-Lan Nguyen/Wikimedia Commons. Shared under CC-BY 4.0 license

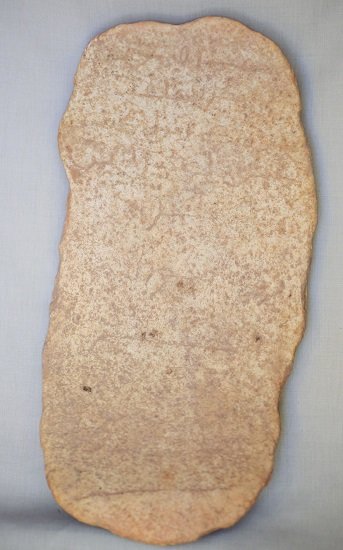

![Grindstone refashioned as a gravestone]() Grindstone refashioned as a gravestone, Tafdit Cemetery, Djebok, Mali, 13th/17th century. Stone, 46.5 x 24 x 7.5 cm. Direction nationale du patrimoine culturel, Bamako, Mali, 2002. Photograph by Seydou Camara

Grindstone refashioned as a gravestone, Tafdit Cemetery, Djebok, Mali, 13th/17th century. Stone, 46.5 x 24 x 7.5 cm. Direction nationale du patrimoine culturel, Bamako, Mali, 2002. Photograph by Seydou Camara

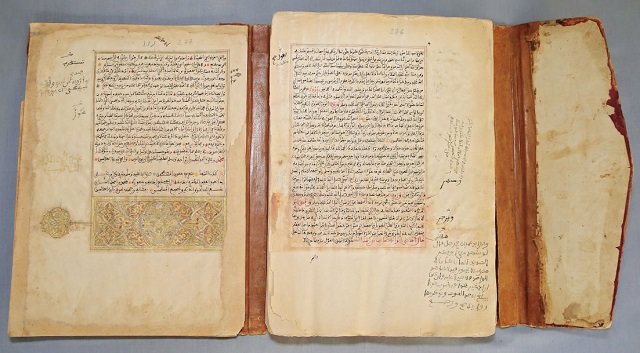

![Al-qadi 'Iyad, The Remedy by the Recognition of the Rights of the Chosen One (Al-Shifta' bi-ta'rif huquq al-Mustafa)]() Al-qadi 'Iyad, The Remedy by the Recognition of the Rights of the Chosen One (Al-Shifta' bi-ta'rif huquq al-Mustafa), North Africa, unknown date. Colored ink and gold on paper, 30.5 x 58 cm. Institut des hautes études et de recherches islamiques Ahmed Baba, Timbuktu, 165. Photograph by Seydou Camara

Al-qadi 'Iyad, The Remedy by the Recognition of the Rights of the Chosen One (Al-Shifta' bi-ta'rif huquq al-Mustafa), North Africa, unknown date. Colored ink and gold on paper, 30.5 x 58 cm. Institut des hautes études et de recherches islamiques Ahmed Baba, Timbuktu, 165. Photograph by Seydou Camara

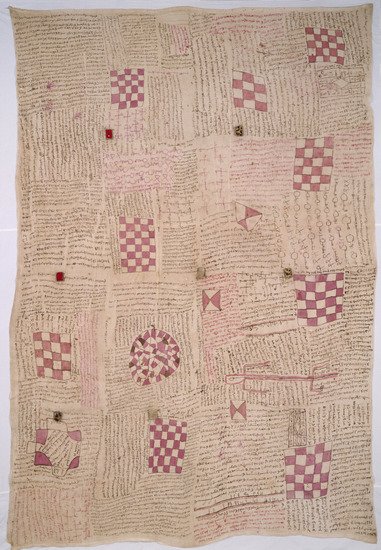

![Talismanic textile. Cotton, plain woven panels (4) joined and painted, with amulets of animal hide and felt attached by knotted leather strips]() Talismanic textile, probably Senegal, late 19th or early 20th century. Cotton, plain woven panels (4) joined and painted, with amulets of animal hide and felt attached by knotted leather strips, 255.2 x 178.8 cm. Art Institute of Chicago, African and Amerindian Purchase Endowment, 2000.326. Photograph courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, NY

Talismanic textile, probably Senegal, late 19th or early 20th century. Cotton, plain woven panels (4) joined and painted, with amulets of animal hide and felt attached by knotted leather strips, 255.2 x 178.8 cm. Art Institute of Chicago, African and Amerindian Purchase Endowment, 2000.326. Photograph courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, NY

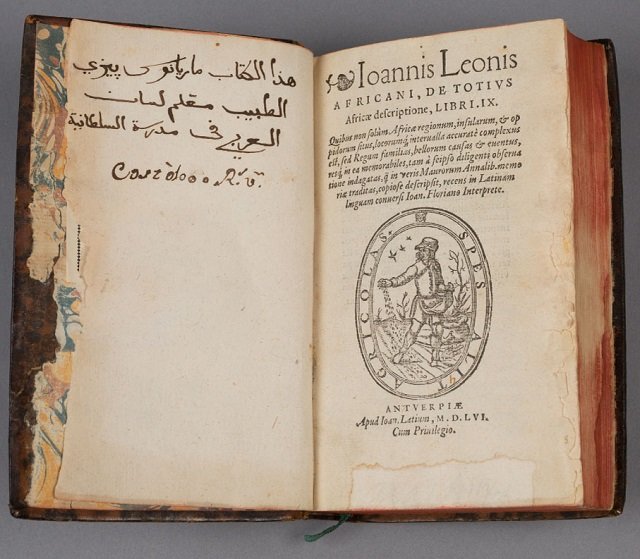

![Leo Africanus]() Leo Africanus, Description of Africa (De totius Africae descriptione). Antwerp, 1556. Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, 916 L576.2. Photograph by Clare Britt

Leo Africanus, Description of Africa (De totius Africae descriptione). Antwerp, 1556. Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, 916 L576.2. Photograph by Clare Britt

Monument from Sane necropolis, Gao, Mali, 12th century. Marble, 87 x 45 cm. Musée national du Mali, Bamako, R88-19-279. © Marie-Lan Nguyen/Wikimedia Commons. Shared under CC-BY 4.0 license

Monument from Sane necropolis, Gao, Mali, 12th century. Marble, 87 x 45 cm. Musée national du Mali, Bamako, R88-19-279. © Marie-Lan Nguyen/Wikimedia Commons. Shared under CC-BY 4.0 license

Grindstone refashioned as a gravestone, Tafdit Cemetery, Djebok, Mali, 13th/17th century. Stone, 46.5 x 24 x 7.5 cm. Direction nationale du patrimoine culturel, Bamako, Mali, 2002. Photograph by Seydou Camara

Grindstone refashioned as a gravestone, Tafdit Cemetery, Djebok, Mali, 13th/17th century. Stone, 46.5 x 24 x 7.5 cm. Direction nationale du patrimoine culturel, Bamako, Mali, 2002. Photograph by Seydou Camara

Al-qadi 'Iyad, The Remedy by the Recognition of the Rights of the Chosen One (Al-Shifta' bi-ta'rif huquq al-Mustafa), North Africa, unknown date. Colored ink and gold on paper, 30.5 x 58 cm. Institut des hautes études et de recherches islamiques Ahmed Baba, Timbuktu, 165. Photograph by Seydou Camara

Al-qadi 'Iyad, The Remedy by the Recognition of the Rights of the Chosen One (Al-Shifta' bi-ta'rif huquq al-Mustafa), North Africa, unknown date. Colored ink and gold on paper, 30.5 x 58 cm. Institut des hautes études et de recherches islamiques Ahmed Baba, Timbuktu, 165. Photograph by Seydou Camara

Talismanic textile, probably Senegal, late 19th or early 20th century. Cotton, plain woven panels (4) joined and painted, with amulets of animal hide and felt attached by knotted leather strips, 255.2 x 178.8 cm. Art Institute of Chicago, African and Amerindian Purchase Endowment, 2000.326. Photograph courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, NY

Talismanic textile, probably Senegal, late 19th or early 20th century. Cotton, plain woven panels (4) joined and painted, with amulets of animal hide and felt attached by knotted leather strips, 255.2 x 178.8 cm. Art Institute of Chicago, African and Amerindian Purchase Endowment, 2000.326. Photograph courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, NY

Leo Africanus, Description of Africa (De totius Africae descriptione). Antwerp, 1556. Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, 916 L576.2. Photograph by Clare Britt

Leo Africanus, Description of Africa (De totius Africae descriptione). Antwerp, 1556. Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, 916 L576.2. Photograph by Clare Britt