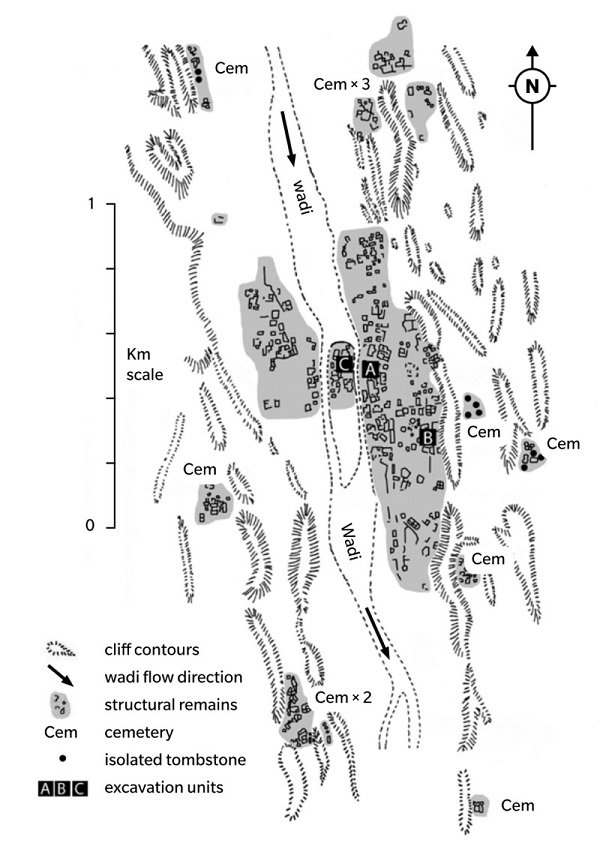

![map of the site of Essouk-Tadmekka]() Schematic map of the site of Essouk-Tadmekka in relation to the surrounding cliffs and the seasonal stream (wadi) that runs through the middle of the site. Identified are the principal zones of the town ruins and surrounding cemeteries. Based on EOM aerial photographs and adapted from Mauny 1961 and Moraes Farias 200313

Schematic map of the site of Essouk-Tadmekka in relation to the surrounding cliffs and the seasonal stream (wadi) that runs through the middle of the site. Identified are the principal zones of the town ruins and surrounding cemeteries. Based on EOM aerial photographs and adapted from Mauny 1961 and Moraes Farias 200313

![Sand Dunes]() Looking down at the Essouk Valley, where the ruins of Tadmekka are located. Photograph by Sam Nixon, 2005

Looking down at the Essouk Valley, where the ruins of Tadmekka are located. Photograph by Sam Nixon, 2005

![Fragments of glazed ceramics (including an oil lamp) excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka. Institut des sciences humaines]() Fragments of glazed ceramics (including an oil lamp) excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

Fragments of glazed ceramics (including an oil lamp) excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

![Stone beads, semi-precious stones, and a cowrie shell excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka]() Stone beads, semi-precious stones, and a cowrie shell excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

Stone beads, semi-precious stones, and a cowrie shell excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

![silk textile]() A fragment of silk textile excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka (3.75 x 2.25 cm). Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

A fragment of silk textile excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka (3.75 x 2.25 cm). Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

![a carved stone torso]() A carved stone torso excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

A carved stone torso excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

![Glass vessel fragments excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photographs by Clare Britt]() Glass vessel fragments excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photographs by Clare Britt

Glass vessel fragments excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photographs by Clare Britt

![Glass fragments from excavations at Essouk-Tadmekka, Mali]() Glass fragments from excavations at Essouk-Tadmekka, Mali. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

Glass fragments from excavations at Essouk-Tadmekka, Mali. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

![Spouted vessel, possibly Egypt or western Asia, ca. 800--1099]() Spouted vessel, possibly Egypt or western Asia, ca. 800/1099. Blown glass, height 6 cm, maximum width 9.9 cm; rim diameter 4.5 cm. Collection of the Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, NY, 63.1.5

Spouted vessel, possibly Egypt or western Asia, ca. 800/1099. Blown glass, height 6 cm, maximum width 9.9 cm; rim diameter 4.5 cm. Collection of the Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, NY, 63.1.5

![Fragment of Qingbai porcelain]() Fragment of Qingbai porcelain (1.48 x 1.74 cm) found at Essouk-Tadmekka, Mali. China, Northern Song dynasty, 10th--12th century. Institut des sciences humaines, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

Fragment of Qingbai porcelain (1.48 x 1.74 cm) found at Essouk-Tadmekka, Mali. China, Northern Song dynasty, 10th--12th century. Institut des sciences humaines, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

![Foliate bowl with stylized peony spray]() Foliate bowl with stylized peony spray, China, Northern Song dynasty, 12th century. Porcelain with underglaze carved decoration, height 7.1 cm, diameter 20.1 cm. Art Institute of Chicago, bequest of Russell Tyson, 1964.847. Photograph courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, NY

Foliate bowl with stylized peony spray, China, Northern Song dynasty, 12th century. Porcelain with underglaze carved decoration, height 7.1 cm, diameter 20.1 cm. Art Institute of Chicago, bequest of Russell Tyson, 1964.847. Photograph courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, NY

![11-unglazed-local-ceramic]() Ceramic fragments from excavations at Essouk-Tadmekka, Mali. Institut des sciences humaines, Mali. Photograph by Kathleen Bickford Berzock, 2016

Ceramic fragments from excavations at Essouk-Tadmekka, Mali. Institut des sciences humaines, Mali. Photograph by Kathleen Bickford Berzock, 2016

Schematic map of the site of Essouk-Tadmekka in relation to the surrounding cliffs and the seasonal stream (wadi) that runs through the middle of the site. Identified are the principal zones of the town ruins and surrounding cemeteries. Based on EOM aerial photographs and adapted from Mauny 1961 and Moraes Farias 200313

Schematic map of the site of Essouk-Tadmekka in relation to the surrounding cliffs and the seasonal stream (wadi) that runs through the middle of the site. Identified are the principal zones of the town ruins and surrounding cemeteries. Based on EOM aerial photographs and adapted from Mauny 1961 and Moraes Farias 200313

Looking down at the Essouk Valley, where the ruins of Tadmekka are located. Photograph by Sam Nixon, 2005

Looking down at the Essouk Valley, where the ruins of Tadmekka are located. Photograph by Sam Nixon, 2005

Fragments of glazed ceramics (including an oil lamp) excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

Fragments of glazed ceramics (including an oil lamp) excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

Stone beads, semi-precious stones, and a cowrie shell excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

Stone beads, semi-precious stones, and a cowrie shell excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

A fragment of silk textile excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka (3.75 x 2.25 cm). Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

A fragment of silk textile excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka (3.75 x 2.25 cm). Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

A carved stone torso excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

A carved stone torso excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

Glass vessel fragments excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photographs by Clare Britt

Glass vessel fragments excavated at Essouk-Tadmekka. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photographs by Clare Britt

Glass fragments from excavations at Essouk-Tadmekka, Mali. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

Glass fragments from excavations at Essouk-Tadmekka, Mali. Institut des sciences humaines, Bamako, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

Spouted vessel, possibly Egypt or western Asia, ca. 800/1099. Blown glass, height 6 cm, maximum width 9.9 cm; rim diameter 4.5 cm. Collection of the Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, NY, 63.1.5

Spouted vessel, possibly Egypt or western Asia, ca. 800/1099. Blown glass, height 6 cm, maximum width 9.9 cm; rim diameter 4.5 cm. Collection of the Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, NY, 63.1.5

Fragment of Qingbai porcelain (1.48 x 1.74 cm) found at Essouk-Tadmekka, Mali. China, Northern Song dynasty, 10th--12th century. Institut des sciences humaines, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

Fragment of Qingbai porcelain (1.48 x 1.74 cm) found at Essouk-Tadmekka, Mali. China, Northern Song dynasty, 10th--12th century. Institut des sciences humaines, Mali. Photograph by Clare Britt

Foliate bowl with stylized peony spray, China, Northern Song dynasty, 12th century. Porcelain with underglaze carved decoration, height 7.1 cm, diameter 20.1 cm. Art Institute of Chicago, bequest of Russell Tyson, 1964.847. Photograph courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, NY

Foliate bowl with stylized peony spray, China, Northern Song dynasty, 12th century. Porcelain with underglaze carved decoration, height 7.1 cm, diameter 20.1 cm. Art Institute of Chicago, bequest of Russell Tyson, 1964.847. Photograph courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, NY

Ceramic fragments from excavations at Essouk-Tadmekka, Mali. Institut des sciences humaines, Mali. Photograph by Kathleen Bickford Berzock, 2016

Ceramic fragments from excavations at Essouk-Tadmekka, Mali. Institut des sciences humaines, Mali. Photograph by Kathleen Bickford Berzock, 2016